I’m not quite sure how I’ve managed to end up in this very specific situation twice thus far in my fairly short career, but here we are. (For context, here is my post from 4 years ago).

The Beginning (redux)

It was a Thursday when I learned I would take over as a 3rd grade teacher for the rest of the school year for a teacher who was going on maternity leave. On a Wednesday, a few weeks later, I was assigned to the school as a substitute paraeducator, and at noon, very unexpectedly, was told okay, it’s happening, and you’re the teacher now. There was some back and forth on whether this was actually true, whether the teacher would return for a couple more days, but come 11pm that night, it was clear *I* was now in charge of this class. While a global pandemic did not shut down our schools the next day, as it did the last time I was in this situation, I still felt far from entirely prepared.

All that to say – this past year (and especially past week) has been a whirlwind.

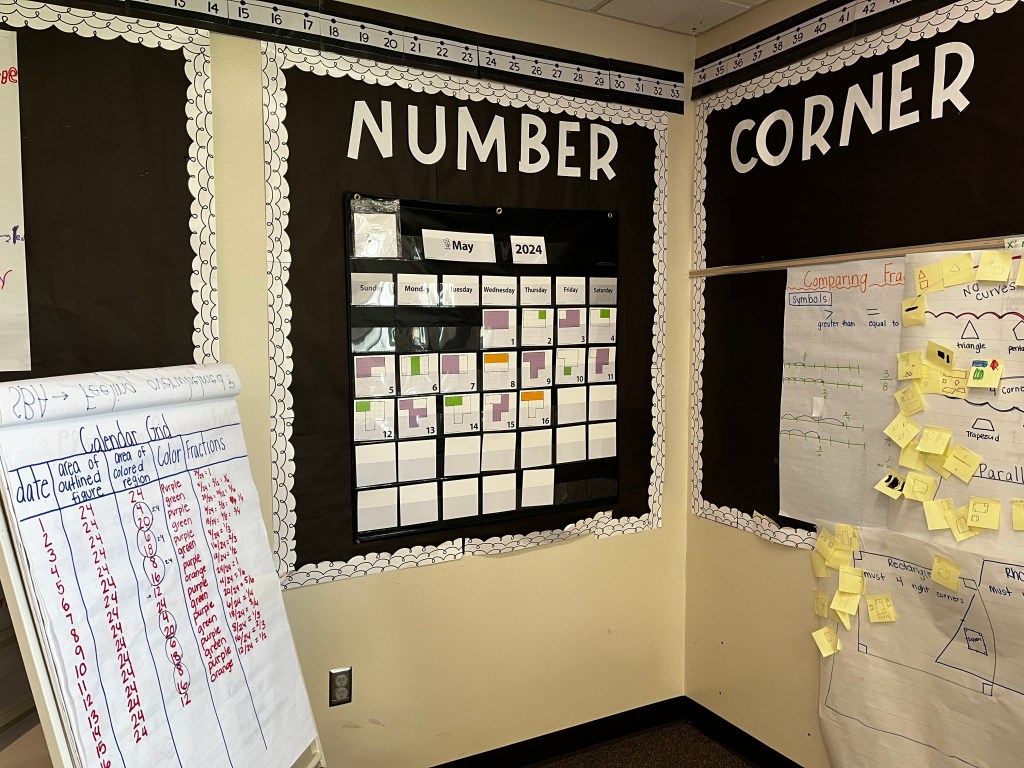

That first half day, going in with absolutely no idea what I was supposed to teach, was an interesting ride, to say the least. Following the general plans as best I could, trying my best to keep a handle on what I’d been told over and over was a very challenging class, I saw that the one academic routine that had been planned for that afternoon was the “Number Corner”.

The Corner of Numbers

I wasn’t super familiar with this routine, which is part of the Bridges in Mathematics curriculum – I had come across it a few times as I subbed across the district, though I spent most of this year teaching & subbing in the subset of schools in this district that use Illustrative Mathematics instead – so again, my understanding was something like – “there’s a calendar with patterns”.

I’m not going to claim to know much more about the idea of Number Corner than that in this post either – this story is really about eliciting and marveling at kids’ mathematical thinking.

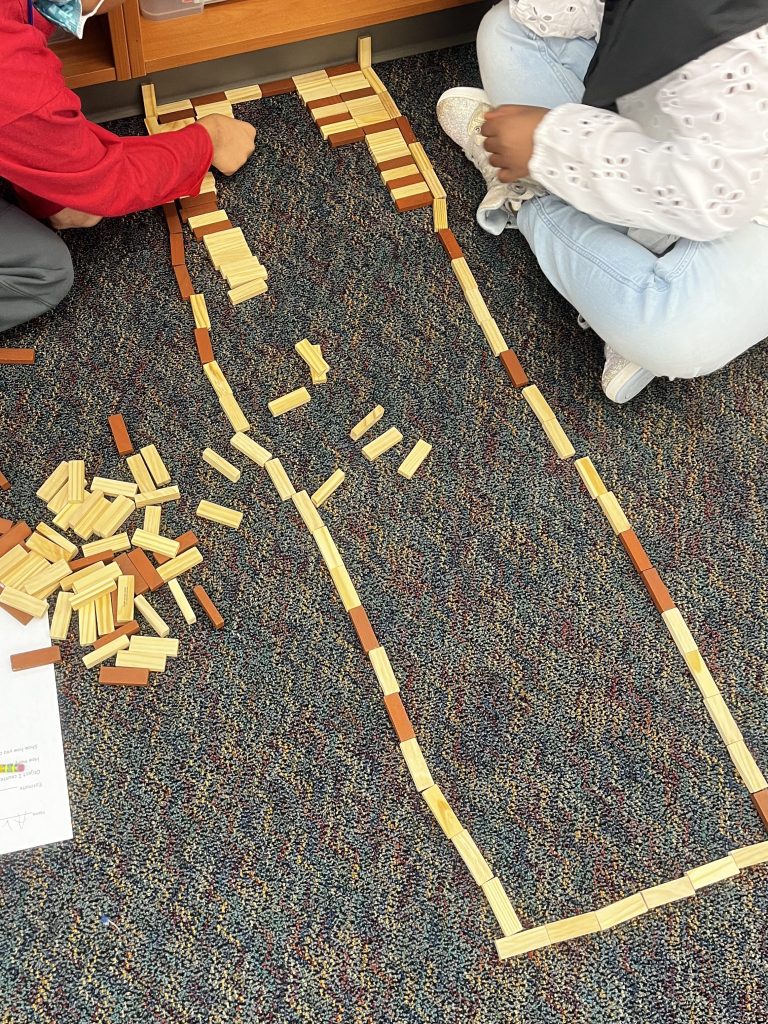

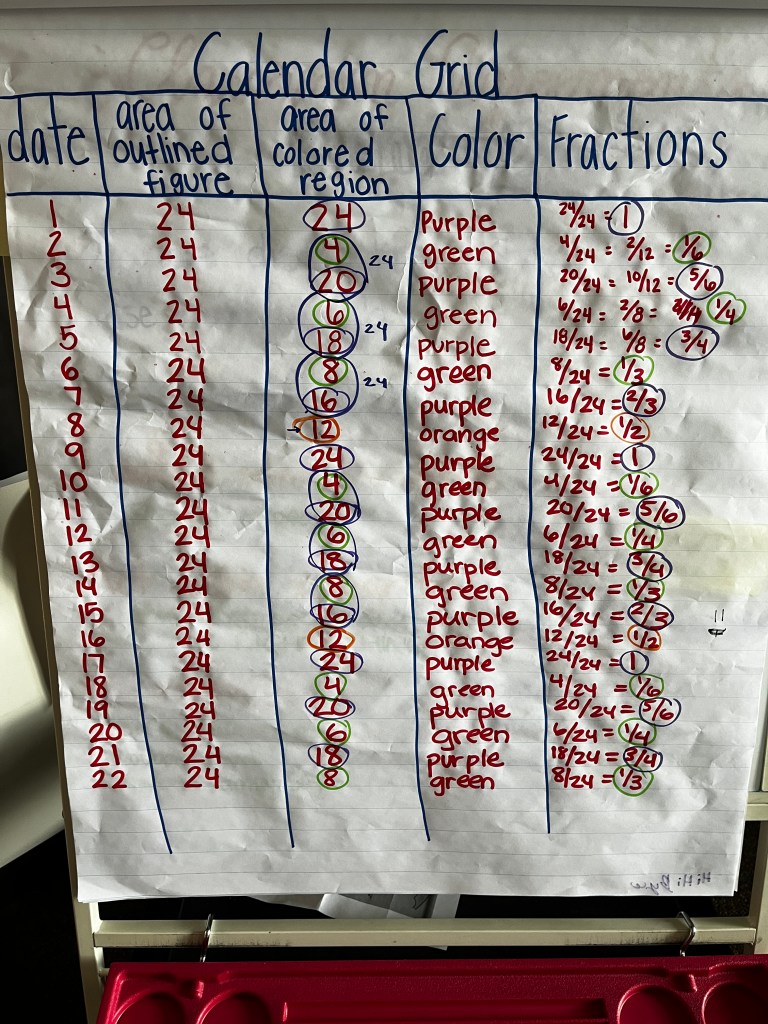

Anyway, back to the story. I told the students it was time for Number Corner, and watched as they all filed into this little corner of the room – some on the floor, some standing behind, some at desks in the vicinity. And then I stepped back to watch them communicate their ideas – the excitement behind the patterns they noticed both in the visual representations on the calendar and the numerical ones on the chart (they hadn’t done it in a few days due to testing, so they were turning around quite a few of the squares).

And so, for a brief moment in the middle of a very, very hectic day, I got to listen to my favorite thing – kids’ thinking about math.

What happened Next

That afternoon, as I was debriefing my day with the principal (and trying to come up with a plan for the next one), she mentioned that the kids had been really engaged in the “math thing” we were doing (she had been in the class watching as we did this routine). At the time, I hadn’t given it much thought – it was on the schedule, I tried my best, kids seemed to enjoy it, but my understanding was that this routine was usually just a quick blip in the day, and sometimes skipped altogether.

It made me think though – what if I approached this routine with more intention? What would I find?

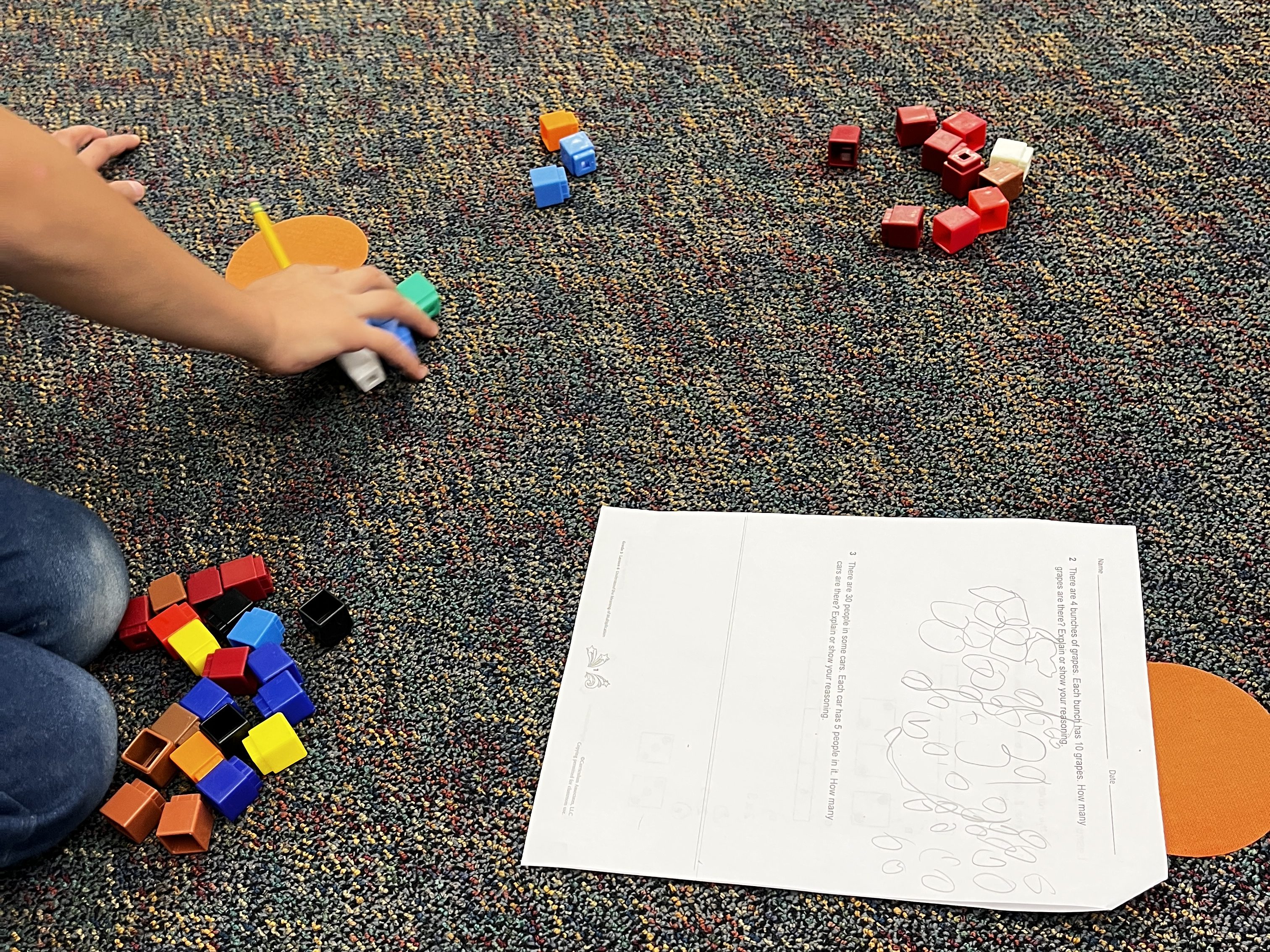

Sometimes, as teachers, we have things that we do in our classrooms because we love them so much, and they give us something in our days/weeks/months to look forward to. For me, that’s always been both “free art with interesting materials” and “free mathematics with interesting materials”. While this doesn’t quite fall into the latter category, “opportunities to see what kids think about math” is definitely a close second.

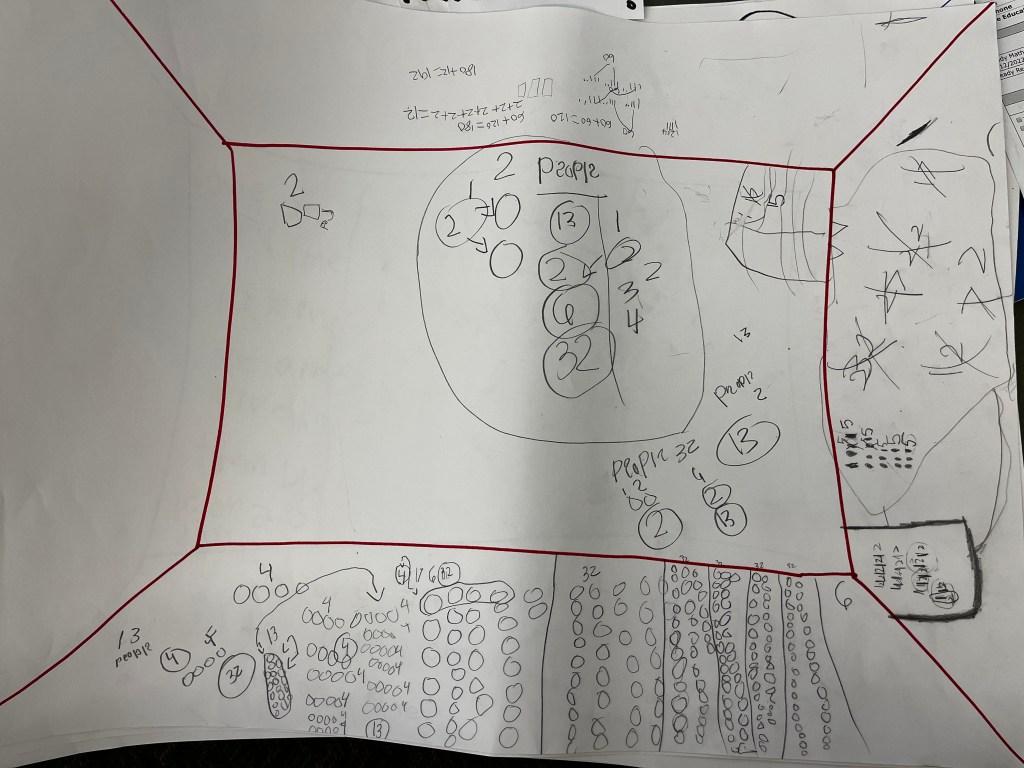

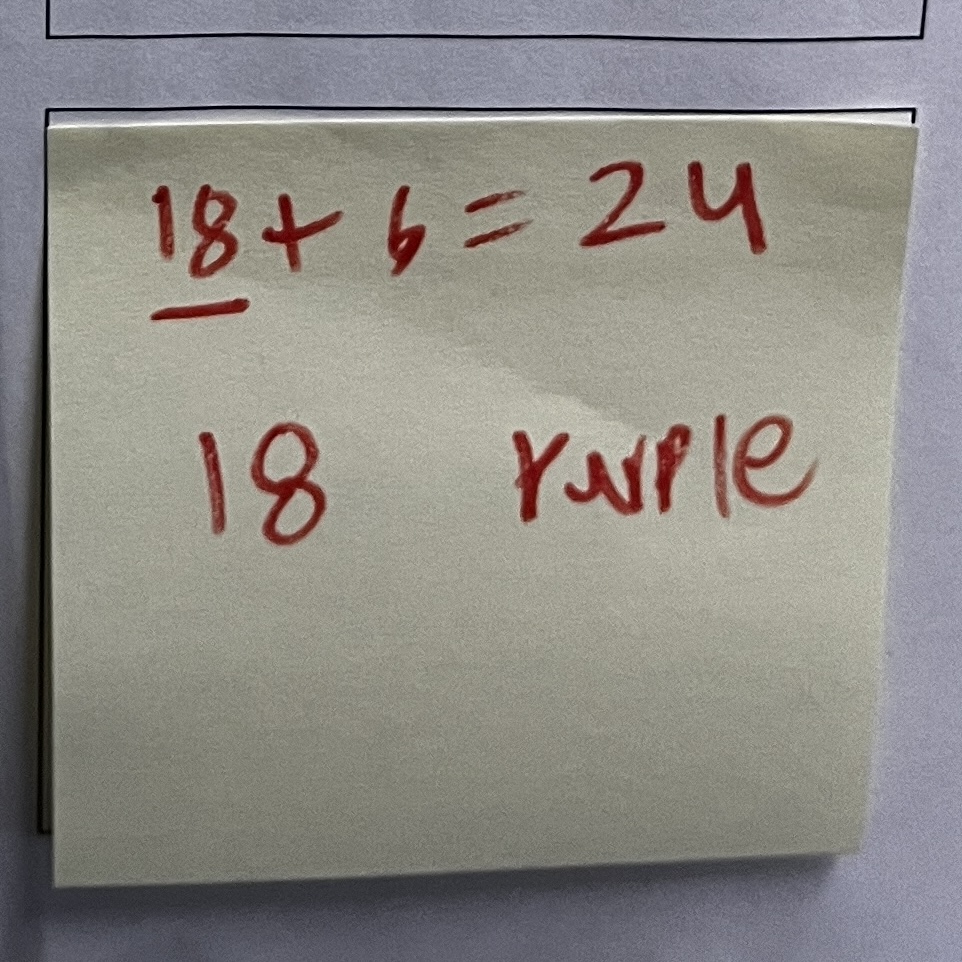

So then, what did they notice? A student I’d struggled to connect with immediately offered her prediction of a cyclical pattern with the fractions (we hadn’t reached the end of the first ‘cycle’ yet). The shock that came with the uncovering of the first orange shape was palpable. There was a lot of conversation attempting to predict when the next orange shape would come – some students thought that every 8 days, there would be a new color introduced. In the days to come, students noticed that the diagonals could be used to predict color and fractions, that every two days the total area added up to 24 (minus a couple outliers), and imagined how the outline of the shape might be manipulated in future dates to preserve the area of 24.

My favorite part is that during this time I can step back, listen, and facilitate/probe when necessary, but otherwise, the students have got it. They’re building on each other’s ideas, calling on each other, turning and talking, and are absolutely devastated if we have to wrap it up before they get a chance to share their idea.

What I’ve found particularly fascinating is that students, as a whole, have been significantly more engaged in our number corner routine than any math lesson we’ve done together* – even with lessons that are meant to be “hands on”, “exploratory”, or “fun”.

*Sidebar to say, they also did love when we played Illustrative Mathematics’ “Mystery Quadrilateral”.

To me, at least, this is a very interesting issue – and I’ll come back to it again in the next section.

For the days remaining in May, I’ve thought about how this routine they’ve already bought into can facilitate further mathematical thinking. Building off this as a warm up or cool down in math, thinking about the possibilities for the next new shape that will appear? Look more closely at the data we’ve collected for new patterns we see? (I’ve been really curious if they’ll make the connection that green < 1/2, orange = 1/2, and purple > 1/2 – or if that’s even an important thing to notice). We’ve tried a few of those ideas, as documented below.

As much as I love being wildly creative in my math routines and lessons, digging deeper, thinking about what new ideas I can try out – it’s also important to step back and realize the power in kids being excited about the math they’re doing – and go from there.

the epilogue (i.e. some random, possibly connected thoughts)

I’ve been reading texts from two math-y authors lately – Is Math Real? by Eugenia Cheng and Ben Orlin’s series of Math with Bad Drawings books. Both authors offer their thoughts on how doing mathematics is quite different than doing mathematics in school. While that sentiment is not new to me, and I’ve certainly made attempts to consider what bringing more of “the approach to mathematics that actual mathematicians use” into my classrooms, there are a couple ideas they put forth that have really elegantly stretched and also simplified my thinking on the math we do in classrooms.

First, Dr. Cheng says that the crux of what mathematics is about, and what mathematicians actually do, is justification (p. 73). As she says, this is the difference between “what is 6 x 8?” and “why does 6 x 8 = 48?” I think students love this routine in part because it requires them to justify their ideas, rather than calculate (similar to a good Which One Doesn’t Belong?). Any task they’re given during class (via the curriculum) is generally asking them to calculate (and sometimes, as a sort of bonus, have some sort of justification for that calculation – but more along the lines of “make sure your answer is correct). I think it’s also a time for students to be able to meaningfully talk to each other about their math ideas in a decidedly non-evaluative and curious way.

Second, in the introduction of the book Math Games with Bad Drawings, Orlin writes that “the secret to our brilliance is that we never stop learning, and the secret to our learning is that we never stop playing.” (p. 11) During the Number Corner, I see students playing with ideas – making conjectures, justifying ideas, creating generalizations out of patterns.

I’m excited to see what June will bring.